Part 2 of 5

(This post was originally appeared in my previous blog in 2016).

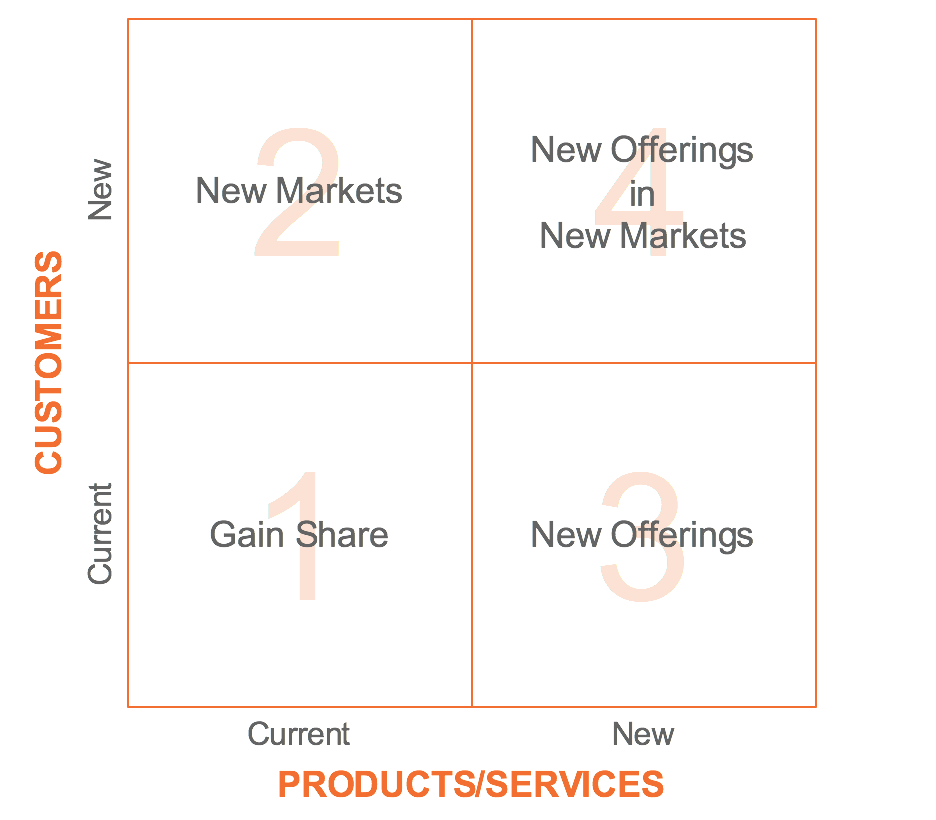

In Your Innovation Roadmap, Part 1, I introduced the innovation matrix (featured above) and covered Quadrant 1: gaining market share. In this post, I’ll cover Quadrant 2: bringing your current offerings to new customers.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Critical to exploring both, Quadrant 2 and Quadrant 3 (bringing new offerings to existing customers), is to identify adjacencies to your core business and exploit those adjacencies by developing a proven, repeatable process. Let’s take a look.

QUADRANT 2: NEW MARKETS

This quadrant is particularly important for startups that have achieved traction with their initial target customer segment and are now looking for new growth opportunities. The natural progression is to identify other customer segments that would find value in your company’s offering. This requires minimal changes to your product/service, while presenting an opportunity to grow revenues. Let’s review a few examples.

Expand Geographies. Uber started with the simple idea of “cracking the horrible taxi problem in San Francisco – getting stranded on the streets of San Francisco is familiar territory for any San Franciscan.” The thing is, getting stranded without easy access to a ride is familiar territory for most people, especially in metropolitan cities like New York, Chicago, London and other cities that rely heavily on taxis and black cars for transportation. So, while Uber launched in San Francisco to solve the taxi problem there, a natural progression for the company was to expand to other markets with similar transportation needs. Eventually, the idea became so prolific that it makes sense to have a presence in any dense, metropolitan area.

So, how does Uber approach geographic expansion? This article on Growth Hackers gives a good in-depth look, but I’ve summarized the key points below, adding in some of my own commentary:

- Accelerants (Common Pain Points). Uber has identified “accelerants” to adoption, which they define as a “concentrated, temporary need for Uber Services” such as restaurants and nightlife, holidays and events, weather and sports. Uber focused expansion on cities where these pain points were consistently high.

- Intense City-by-City Launches. Uber customizes a new city launch based on the city’s unique topography, suppliers, special interest groups and culture. This includes hiring a local, entrepreneurial person to lead the city’s launch.

- Free Rides. Is there an easier way to get people to try your product than offering a free trial? A significant share of Uber’s funding has gone towards subsidizing free rides in new markets or discounted rates on rides.

- Wow Experience. Getting started as a rider on Uber is dead simple. The product works seamlessly. And, it’s comparably simple to join as a new driver. One key metric to success has been reaching a driver saturation point where Uber can get a car to you within 3 minutes. Anyone that has tried hailing a cab during a shift change knows how valuable this is.

- Experiential Word-of-Mouth. The above points all contribute to a word-of-mouth machine. Uber is a two-sided marketplace that, for all intents and purposes, is the Facebook of the physical world – achieving viral growth through word-of-mouth. I’d bet that most people first learn about Uber through a referral or, as I did, traveling to cities like San Francisco and NY and experiencing Uber before it reached my city of Austin. By the time Uber decides to enter a city there is pent up demand. Uber uses this demand, and its high public profile, as leverage against local lobbyists and legislators to drive changes in laws to allow TNCs (transportation network companies) to operate within the city. Most of the time, this works. But, as we saw recently in Austin, this isn’t always the case. In Austin, both the City Council and Uber mismanaged the situation, and local citizens paid the price in seeing Uber and Lyft leave the city limits.

Expanding geographic markets is a natural way to grow a business that offers products/services of broad appeal.

Expand Up/Down the Buyer Value Chain. Great companies are built by solving a very particular problem for a specific customer in mind. This is particularly true in tech. Often times, the problem is a pain point that the founder has personally experienced and decided to tackle him/herself. And, thus, the company targets a specific audience (customer) with its first product, builds traction and word-of-mouth, while gathering customer feedback, from that audience, before expanding to other audiences.

The idea of the buyer value chain is that different customer segments have different adoption rates and appetites for paying for a product/service. A company may create a product with an customer in mind. But, the company should then look up the buyer value chain to identify audiences that may be willing to pay more for the product with minor enhancements (a higher margin/lower volume play), and down the buyer value chain to identify customers that may be willing to pay less for a product with less features (a lower margin/higher volume play).

SaaS (software as a service) businesses do this well – particularly around the freemium business model. Freemium is a business model where the company offers a low-cost version of its product/service for free, then offers enhanced versions with additional features or services at a premium (i.e. for a price). The pricing model is tiered, such that the more features/services the higher the price. Conceptually, the idea is that 80% of your customers may use the free version, but 20% will pay for the premium versions. And, that revenue will more than make up for the cost of offering the free version. Valuable businesses have been built off of this model.

One example is New Relic, which started by providing its analytics platform to Ruby on Rails developers because that was a growing, underserved community of developers that were innovative and vocal about products they liked (and disliked). After gaining traction with this community through a freemium model, they expanded to developers using other programming languages. Founded in 2008, New Relic’s market cap is now hovering around $1.64B (as of this writing). Clearly, it’s come a long way from its original focus on Ruby on Rails developers.

Other software businesses have followed a similar approach with freemium. Box started by offering 1GB of virtual storage for free. Individual customers using more storage had to pay for it. And, businesses that reached a threshold of employees using the product, also had to pay for it. Since, customers signed up for a Box account with their email address – usually using their business email – Box has been able to identify companies that had a growing number of employees using the product. This was a critical strategy: infiltrate enterprises by targeting the individual employee and gaining word-of-mouth and adoption within that employee’s company. Then, once that employee’s company reach a threshold of people using Box with the company’s email domains, Box used this as leverage to sell that company’s IT team a premium, enterprise version of Box that consolidated employee accounts into a secure system managed by the IT team. Slack, potentially that fasted growing B2B tech company in history, has used this same strategy: offer free, basic versions of the product to individual customers at the bottom of the buyer value chain; offer paid versions of the product with more storage space to individual customers further up the buyer value chain; and, finally, offer enterprise level versions of the product to businesses at the top of the buyer value chain.

The auto industry also gives us an example of how to expand up/down the buyer value chain. The chassis is essentially the car’s skeleton. Large multi-brand automakers like General Motors will design a new chassis, and then implement it across brands. For example, the Chevy Suburban, GMC Yukon XL and Cadillac Escalade each target a different customer segment, but share the same chassis. Similarly, the Chevy Traverse, Buick Enclave, and GMC Acadia share the same chassis. What differentiates these cars are the exterior designs, price points and associated brands – each targeting a different customer segment along the buyer value chain. Chevy is the everyman American’s brand. GMC is the higher end, professional grade brand. Buick is the economic luxury brand. And, Cadillac is the aspirational luxury brand.

Similarly, Tesla, after launching in Quadrant 4 (as most tech startups do), is deploying a Quadrant 2 growth plan that started at the top of the buyer value chain and is moving downwards over time. In a brilliant strategy, Tesla first launched with its Roadster – a $100,000, limited edition, high performance sports car – in order to build an aspirational brand with wealthy, highly visible and influential customers. This strategy allowed Tesla to, essentially, sell prototypes of very expensive electric vehicle (EV) technology, build word-of-mouth and demand, and begin to bring down the cost of the EV technology. Its next product, the Model S, leveraged improved technology at more efficient costs to offer the vehicle at a reduced price of around $70,000, targeting high end luxury sedan buyers. Next on the product roadmap are the Model X, Tesla’s first SUV offering, and the Model 3 – a more affordable sedan. With each of these products, Tesla creates offerings further down the buyer value chain.

Expand Industry Verticals. Finally, a key opportunity to bring your current offerings to new customer segments is by expanding into new industry verticals. Nike serves as an exceptional example of Quadrant 2 (and Quadrant 3) innovation strategy in the consumer goods and athletics space. The quote below from this Harvard Business Review article summarizes Nike’s approach:

“Nike begins by establishing a leading position in athletic shoes in the target market. Next, Nike launches a clothing line endorsed by the sport’s top athletes—like Tiger Woods, whose $100 million deal in 1996 gave Nike the visibility it needed to get traction in golf apparel and accessories. Expanding into new categories allows the company to forge new distribution channels and lock in suppliers. Then it starts to feed higher-margin equipment into the market —irons first, in the case of golf clubs, and subsequently drivers. In the final step, Nike moves beyond the U.S. market to global distribution.”

As you can see, Nike begins with Quadrant 2 strategy, adapting its core product (the athletic shoe) for a new customer segment (golfers) in a familiar geographic market (the U.S.). It uses endorsement deals to gain visibility and credibility in this new segment (just as Tesla used wealthy, influential Roadster customers to build its brand reputation in the auto industry). Nike also uses this time to adapt its business model for the segment by solidifying distribution channels and suppliers. Then, Nike moves into Quadrant 3 strategy, offering the golf segment more products such as a clothing line, balls and clubs. Once Nike successfully adapts its business model for the new segment and gains market share in that segment, all the while building word-of-mouth and pent up demand for its new products outside of the U.S., Nike shifts back into Quadrant 2 strategy, offering its full golf product line to new customer segments outside the U.S. market. This is a proven, repeatable process that Nike has deployed time and again to enter new verticals within the athletics industry.

B2B companies frequently use a similar innovation and growth approach. Often times a tech company begins by developing its technology for a specific industry. But, over time, as the company’s market share gains (Quadrant 1) level out, and the company looks for new growth opportunities, a natural progression is to find other industries that share similar characteristics with those of its core industry. Then, the company can adapt its technology and messaging to expand into those adjacent industries. For example, a company that services the highly regulated health care industry, might naturally expand to adjacent industries that are also regulated, such as financial services or energy.

QUADRANT 3: NEW OFFERINGS

In the next post in this series, I’ll cover Quadrant 3 strategy. As you may have noticed in this post – particularly the Nike example – Quadrant 2 naturally progresses in to Quadrant 3 and vice versa.

To read about Quadrant 1 – grow market share – click here.

(This post was originally appeared in my previous blog in 2016. I posted it here because the Innovation Roadmap Framework is timeless and still relevant today in 2024—though this post could be updated with some newer examples. If you have examples of companies that fit the Gain Share quadrant, and you’d like me to write about it, let me know in the comments.)