Part 1 of 5

(This post was originally appeared in my previous blog in 2016).

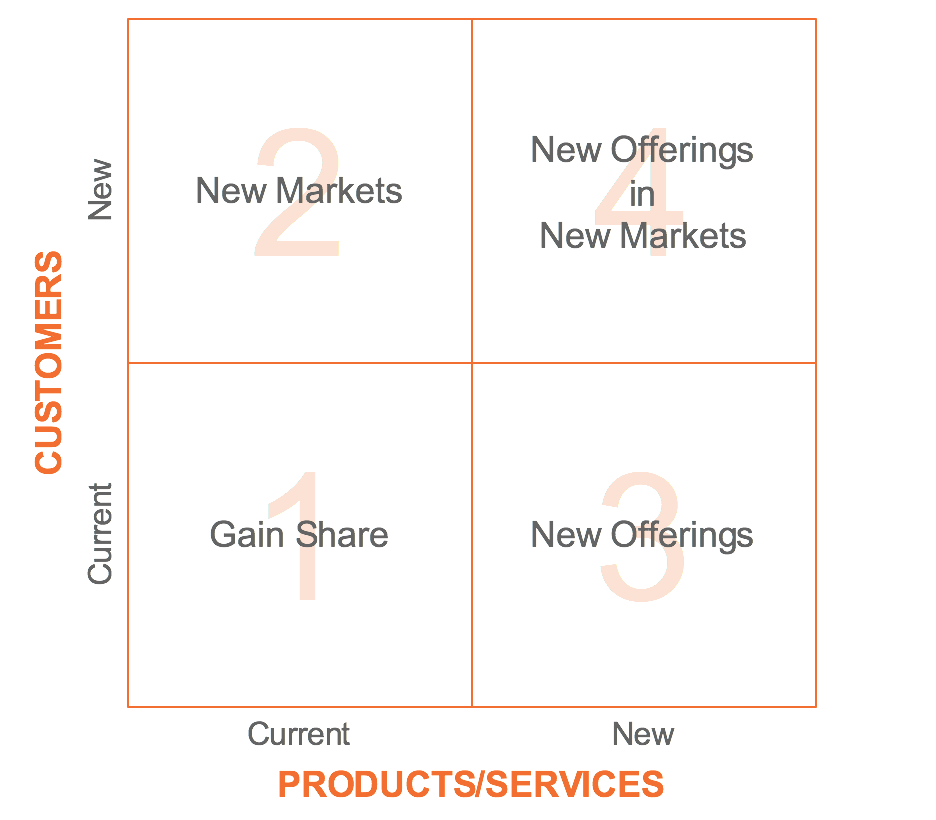

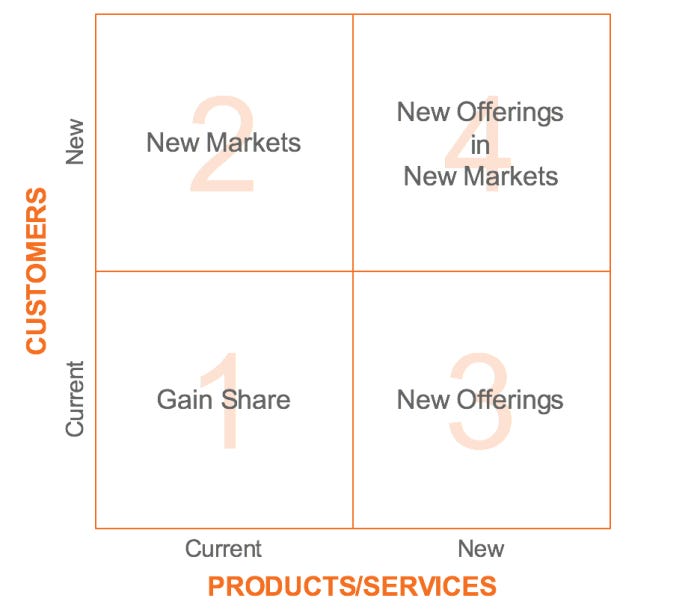

Your innovation roadmap is critical to the value of your business, as companies are valued based on their ability to generate cash flows in the future. In the simplest of terms, when investors are placing a value on your company, they are looking at your historical growth, likely over the previous five years, as measured in CAGR (compound annual growth rate), and then estimating out your future growth over the next five, ten or more years, depending on your company’s industry and stage. As such, it’s critical to understand where your growth is coming from. Luckily, getting started is relatively simple: refer to the matrix below:

Growth typically comes from one of four places:

- Taking market share in areas where you already compete,

- Offering your current products/services to new customer segments,

- Offering new products/services to your existing customer segments, or

- Offering new products/services to new customer segments.

You can typically place innovation in one of two buckets:

- Incremental – where you are adding onto, or improving, an existing innovation

- Discontinuous – where you are taking an entirely new leap

Incremental innovation, which is represented in quadrants 1 – 3 of the innovation/growth matrix, is considerably easier and more linear of a path. Discontinuous innovation, represented in quadrant 4 of the innovation matrix, is much harder and likely requires more capital investment over a longer period of time. It also gets into organizational design issues that I’ll save for a future post. Let’s discuss Quadrant 1.

QUADRANT 1: GAIN SHARE

There are several ways to gain share in markets where you already compete. I’ve listed five examples below:

Advertising & PR. Increasing your spend on advertising and public relations is one way to gain share. A wonderful example of this is Virgin Atlantic’s response to the 2008 recession. In a time when Virgin Atlantic‘s main competitor, British Airways, was cutting back on marketing spend, Virgin Atlantic increased its marketing spend by 10%, investing in a new advertising campaign to celebrate its 25th birthday. This campaign alone is estimated to have driven 20% of revenue during the period in which the campaign was running with a return on investment of £10.58 for every £1 spent on the campaign. British Airways, which cut back on marketing expenses during this period, reported a £400M operating loss, while Virgin Atlantic reported a £68M operating profit.

Compete On Price. I’m not a fan of this strategy for businesses selling high value products/services, as it dilutes brand value and sets a precedent for future price cuts. Typically, if a customer is basing its purchase decision primarily on price, one of two underlying issues exists: (1) the company has not differentiated itself enough for the customer to understand why they should pay a premium for the company’s product/service, or (2) the customer actually isn’t the company’s target customer. Apple was once the case study for this. They are positioned as a premium brand, and thus, their customers were willing to pay the higher price for a desktop, laptop, iPhone, iPad or Apple Watch, compared with a Windows desktop or laptop, or an Android phone, tablet or smart watch. But, as Apple continues to offer versions of their products at lower prices, targeting a broader customer segment, they will dilute their brand. They may gain share, but they will lose leverage. This also brings Apple into a different growth strategy: offering existing products to new markets (Quadrant 2 in the matrix).

That said, many industries and brands choose to compete on price. This is a typical strategy for retailers, both brick and mortar and e-commerce, as well as the travel industry. Companies like Amazon, Walmart, Target and Best Buy consistently compete on price, operating on razor thin margins. The airline industry also defaults to hyper-competition on price. But, as witnessed in the above referenced case on Virgin Atlantic vs. British Airways, it doesn’t have to be this way. British Airways chose to compete on price, diluting its brand and leading it to an operating loss, whereas Virgin Atlantic chose to invest in advertising, building its brand and leading it to an operating profit.

Technical Innovation. Shipping incremental improvements on your products/services can steer customers, who place a premium on technology, quality and experience, your way. This is certainly the case for the high tech industry which has grown accustomed to an accelerating cadence of software and hardware updates, but can also be found in industries like consumer packaged goods. Take men’s razors for example. For a century, companies like Gillette, Schick and BiC have competed on patent innovation. Each brand adds an extra razor, or makes its razors thinner, or adds lubrication and skin protection, giving consumers the illusion of getting a better shave. The reality is that many of these razors, and the close shaves they offer, lead to irritation and razor bumps – particularly in minorities like blacks and hispanics. Thus, an opportunity opened up for brands like Bevel to come in with better shaving experiences, including a return to the single-blade safety razor. Deodorant is another interesting consumer product these days. I can understand 24-hour protection like Degree offers. But, Right Guard has taken their innovation to another level, offering deodorants with 72-hr and even 96-hr protection. I’d love to see the research that led to the insight that men need 4 days worth of odor protection at a time. But, I digress…

Acquisitions. Acquiring competitors is another way to gain share. This is a simple assumption. When you acquire a competitor, you can expect that (most of) their customers come with it. Just be conscious that most firms don’t capture the full potential value of the transaction. See Jack Welch’s post here on the Six Deadly Sins of M&A for some guidance.

Acquisitions. Acquiring competitors is another way to gain share. This is a simple assumption. When you acquire a competitor, you can expect that (most of) their customers come with it. Just be conscious that most firms don’t capture the full potential value of the transaction. See Jack Welch’s post here on the Six Deadly Sins of M&A for some guidance.

Customer Service/Experience. So many brands think of customer service as a nuisance. Entire operations are based on minimizing the amount of time that a customer service representative spends on the phone with a customer, or a sales representative spends on the floor with a customer. But, valuable businesses have been built on extraordinary customer service and experiences: Virgin, Apple, Southwest Airlines, Zappos, Nordstrom and Rackspace to name a few. In fact, many of today’s high growth startups and unicorns are founded on the basis of offering customers a better experience than what exists in an entrenched market – Uber, Lyft, Airbnb, Wealthfront and StitchFix come to mind.

What strikes me is that gaining share has so much to do with brand building activities. These activities, which include the above examples of investing in advertising and PR, in technical innovation, in (thoughtful) acquisitions, in customer service/experience, and maintaining a brave pricing strategy are all value creating strategies. But, in today’s world of financial engineering and focus on short-term gains, leaders of publicly held companies have a tough time investing in these growth activities. No wonder we see more innovation coming from private companies.

To read about Quadrant 2 – new markets – click here.

(This post was originally appeared in my previous blog in 2016. I posted it here because the Innovation Roadmap Framework is timeless and still relevant today in 2024—though this post could be updated with some newer examples. If you have examples of companies that fit the Gain Share quadrant, and you’d like me to write about it, let me know in the comments.)